Recently, The New York Times “California Today” column updated readers on the latest additions to California’s list of official state symbols:

On Jan. 1, the pallid bat, or Antrozous pallidus, and the California golden chanterelle, or Cantharellus californicus, joined the long list of symbols. The designations are intended to promote their appreciation, study and protection in the state, according to the wording of the laws that gave them their official status.

It never occurred to me that California needed an official state bat nor an official state mushroom, but here we are. According to the State Symbols online exhibit of the Capitol State Museum, state symbols range “from plant species to marine life, from songs to nicknames, from ghost towns to memorials.” The diversity is staggering, and I imagine that the curators of the exhibit found the challenge of categorizing the symbols—including adding a bat and a mushroom—daunting. But according to this exhibit, one California symbol stands out among the dizzying array:

Among those natural symbols is one of California’s most recognizable: the California grizzly, which in addition to being featured on two of the oldest and most prominent of our symbols, the State Flag and the State Seal, has also become a large part of our collective identity as a state.

That’s exactly right, but it’s an uncomfortable fact, given that the last of the California grizzly bears disappeared from the Golden State way back in the 1920s.

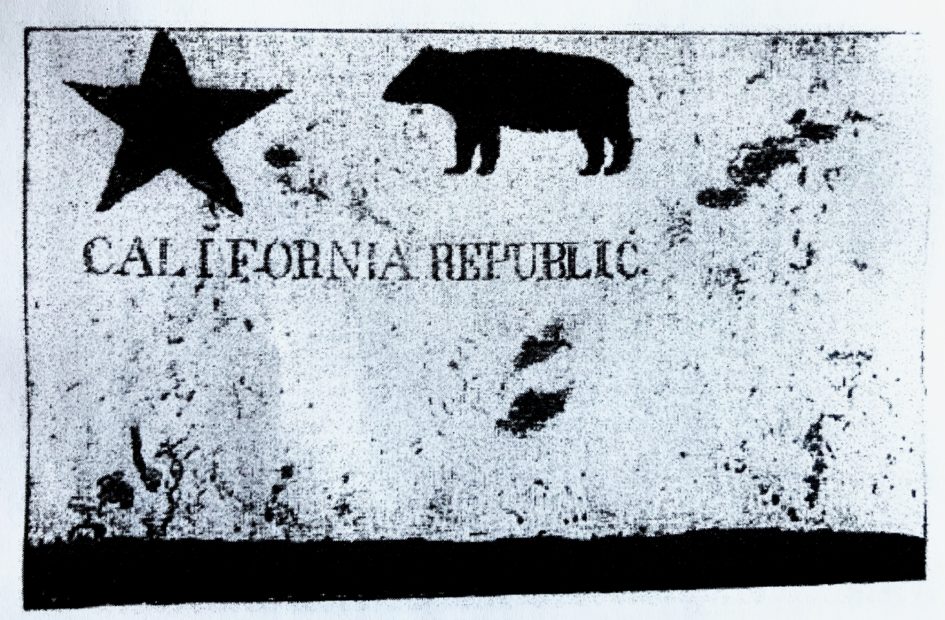

The appearance of the California grizzly on an early version of our current flag was not auspicious. In 1846, a group of twenty-four Americans, living within what was then Mexican California, proclaimed California an independent republic. Members of the so-called Bear Flag Revolt, with murky support lent by “Pathfinder” Major John C. Fremont, rightly anticipated that California would eventually become part of the United States. Their banner, designed by one William C. Todd (nephew to Mary Todd Lincoln, it turns out) featured a star at the upper left corner faced by a grizzly bear rendered in brown paint. The flag was raised at Sonoma, ground zero for the revolt. But, as recalled by early California pioneer John Bidwell, there was a catch:

Among the men who remained to hold Sonoma was William B. Ide, who assumed to be in command. In some way (perhaps through an unsatisfactory interview with Frémont which he had before the move on Sonoma) Ide got the notion that Frémont’s hand in these events was uncertain, and that Americans ought to strike for an independent republic. To this end nearly every day he wrote something in the form of a proclamation and posted it on the old Mexican flagstaff. Another man left at Sonoma was William L. Todd, who painted, on a piece of brown cotton, a yard and a half or so in length, with old red or brown paint that he happened to find, what he intended to be a representation of a grizzly bear. This was raised to the top of the staff, some seventy feet from the ground. Native Californians looking up at it were heard to say “Coche,” the common name among them for pig or shoat. (520)

I’m sure Todd meant no disrespect to either bears or pigs. And today, our California flag, adopted in 1911 (with final design approved in 1953), retains his basic plan. Though there’s nothing porcine about the California bruin on the current flag, the flat, almost cartoon-like rendering still doesn’t do justice to the majesty of Ursus arctos californicus. Perhaps it’s too much to expect anything different, given the medium, but as depicted on the flag, the grizzly’s sort of sly, “What, me?” look suggests a hapless bear that got caught with its claws in the pudding bowl rather than a symbol of ferocious tenacity.

Fortunately, the bear sketches penned by master showman and gifted writer Joaquin Miller in his 1900 book True Bear Stories tell a fuller story. At the same time they do a credible job anticipating the sad trajectory of the California grizzly’s fate. Some of Miller’s sketches even recall experiences with California bears that take place not long after Todd was wetting his paint brush.

Joaquin Miller was a nom de plume suggested by Miller’s friend, poet Ina Coolbrith, to conjure a bit of the romance associated with California’s legendary bandit Joaquin Murrieta. For a while, Miller was a well-known showman, strutting stages in Europe, garbed in western gear, declaiming his verse with memorable panache, and earning acclaim as the “Poet of the Sierra.” But his more lasting contributions to American letters were in prose, much of it lamenting the depredations of white miners and settlers upon the indigenous peoples of California. His best known work is the loosely autobiographical social novel Life Amongst the Modocs: Unwritten History (1873). While Miller’s book often stretched the truth, it included valuable and vivid descriptions of life in northern California as he experienced it in the mid-nineteenth century. True Bear Stories is less overtly a muckraking work than Modocs, but embedded within the bear lore is a tale that parallels Modocs’ basic motif, the unsettling changes wrought by the American conquest, changes that, as it turned out, endangered habitat for California’s iconic symbol, the grizzly bear, but also devastated the forest ecology of northern California.

The sketch “Bear on Fire” appears near the beginning of the Bear Stories collection, relating how Miller served as a guide for two English artists keen on exploring the Mount Shasta region, “the fish, game, scenery and excitement and everything , in fact, that was in the adventure” (14). Unfortunately, the party was suddenly threatened by a raging forest fire that swept across the terrain threatening not only Miller and his companions, but most of the wildlife nearby. Miller recalls that near the McCloud River came “a torrent of little creeping things: rabbits, rats, squirrels! None of these smaller creatures attempted to cross, but crept along in the willows and brush close to the water” (21). The sketch ends with an unbelievable sight: “Over our heads like a rocket, in an instant and clear into the water, leaped a huge black bear, a ball of fire! his fat sides in flame” (26). Given Miller’s reputation for exaggeration, I’m not sure whether to believe the part about the flaming bear, but I tend to accept his overall description; if nothing else, it serves as a literary precursor to Robinson Jeffers’ “Fire on the Hills,” which tells a similar story.

Earlier in the tale, almost in passing, and easy to forget after reading about a burning bear, Miller recalls how native people seasonally managed northern California forests, partly with the use of fire. With the encroachment of settlers, they were no longer able to do so: “When a lad I had galloped my horse in security and comfort all through this region. It was like a park then. Now it was a dense tangle of undergrowth and a mass of fallen timber. What a feast for flames!” (15-16). The result: “and here we were tumbling over and tearing through ten years’ or more of accumulation of logs, brush, leaves, weeds and grass that lay waiting for a sea of fire to roll over all like a mass of lava” (16).

“The Grizzly As Fremont Found Him” comes later in his arrangement of bear tales, but serves, I think, as useful punctuation for Miller’s alarm over the effects of white settlers on the region. In Miller’s view, one result is the loss of traditional means of managing the forests, which allows for hotter, more dangerous fires. Another result, is that the settlers were often blind to how their activities changed ecological niches that supported local wildlife, including grizzly bears, which, thanks to their reputation for ferocity, were badly misunderstood:

In the early ’50s, I, myself, saw the grizzlies feeding together in numbers under the trees, far up the Sacramento Valley, as tranquilly as a flock of sheep. A serene, dignified and very decent old beast was the full-grown grizzly as Fremont and others found him here at home. This king of the continent, who is quietly abdicating his throne, has never been understood. The grizzly was not only every inch a king, but he had, in his undisputed dominion, a pretty fair sense of justice. He was never a roaring lion. He was never a man-eater. He is indebted for his character for ferocity almost entirely to tradition, but, in some degree, to the female bear when seeking to protect her young. Of course, the grizzlies are good fighters, when forced to it; but as for lying in wait for anyone, like the lion, or creeping, cat-like, as the tiger does, into camp to carry off someone for supper, such a thing was never heard of in connection with the grizzly. (113-14)

Perhaps the “king of the continent” might have done better in California if more fully understood. But probably not. Miller saw pretty clearly what was to be the grizzly’s fate, the twin scourges of expanded settlement and accompanying self-interest:

The grizzly went out as the American rifle came in. I do not think he retreated. He was a lover of home and family, and so fell where he was born. For he is still found here and there, all up and down the land, as the Indian is still found, but he is no longer the majestic and serene king of the world. His whole life has been disturbed, broken up; and his temper ruined. He is a cattle thief now, and even a sheep thief. In old age, he keeps close to his canyon by day, deep in the impenetrable chaparral, and at night shuffles down hill to some hog-pen, perfectly careless of dogs or shots, and, tearing out a whole side of the pen, feeds his fill on the inmates. (114-115)

According to Brent Crane, writing for Discover Magazine, “The last resident bear, reportedly spotted in 1924, was also the last of its subspecies: Ursus arctos californicus. These California grizzlies had reached an estimated population of 10,000 before Europeans arrived and triggered their steady demise.”

The neglect of forest management that Miller complained of decades ago is the precursor of misconceived fire suppression policies that, when possible, sought to eradicate most all wild fires, leaving forest floors thick with flammable fuels and dotted with timber not yet mature enough to resist spreading flames that can climb up young trees into forest canopies that might otherwise have been safer. The indifference toward the survival of the grizzly is of like origin. Not precisely malign but often fueled by perceptions of short-term interests that made it easy to accept the eradication of an immediate threat. Thus in Miller’s account, a lack of foresight led to the twin catastrophes of misconceived forest management practices and the eradication of a dominant species have left the wilderness worse off.

The problem of flawed fire suppression strategies, however, is in some spaces being forthrightly addressed, partly thanks to native people who are heirs to the kinds of forest practices that Miller so sorely missed. For example, A-dae Romero-Briones, Enrique Salmon, Hillary Rennick, and Temra Costa have written that many conservationists are embracing the idea that human communities can serve as keystone species in some ecologies, “as saguaro cacti are to the Sonoran Desert or Oak trees are to the California landscape.” They describe how the Karuk Nation works with the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Indian Affairs Fire Management to conduct low intensity burning of underbrush:

Tending the land, walking upon the land, coppicing and pruning traditional plants, burning the underbrush, and gathering and hunting important foods and cultural materials – all this and more is the manifestation of a human/nature-centered relationship. It is through physical activity and sustenance that unprecedented understanding of the cycles of the environment can be strengthened through consistent practice and over generations.

The problem of the loss of the grizzly may be less tractable, partly because the state’s wildfire problem is, thanks to climate change, levels of magnitude more concerning and partly because the likely outcomes of reintroducing the bears here are so speculative. According to Crane, recent studies have examined the effects of introducing some of the California grizzly’s brown bear cousins that are beginning to overpopulate protected places like Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks. The idea isn’t only to take pressure off the parks, but possibly to improve the ecological balance in remote areas of our state. But the likelihood of reintroduction seems slim. Crane quotes a spokesperson for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife who says that the department “is already inundated with human-wildlife interactions with the [animal] species that are here. . . . We have no reason to assume that grizzlies would stay within some arbitrary boundary we set in a remote area of the Sierra.”

Miller’s bear stories present long ago aspects of grizzly life alongside a prescient awareness of the harm loss of indigenous practices has led to. But for now, it seems clear that California’s state flag (and its seal) will continue to recall for some of us the eradication here of a magnificent species. I’m not sure if that’s a good thing.

Sources

Beers, Terry. “History as Fiction: The California Social Novel.” Cal@170: 170 Stories Celebrating the State of California’s First 170 Years. The California State Library. https://cal170.library.ca.gov/history-as-fiction-the-california-social-novel/?fbclid=IwAR0bSN3WtBgmDJ3XsGrPoA5nc8LUQ1SgnYnk7t5B38WncsSugm9YsuEH-rs. Accessed 16 Feb. 2024.

Bidwell, John. “Frémont in the conquest of California.” The Century Magazine, February, 1891, pp. 518-540. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112076865440. Accessed 7 Feb. 2024.

Crane, Brent. “Grizzly Bears Might Return to California. Is the State Ready?” Discover. 20 Dec. 2019. https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/grizzly-bears-might-return-to-california-is-the-state-ready. Accessed 12 Feb. 2024.

Karlamangla, Soumya. “California Now Has a State Mushroom and a State Bat.” The New York Times. 18 Jan. 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/18/us/california-state-symbols-bat-mushroom.html. Accessed 5 Feb. 2024.

Miller, Joaquin. True Bear Stories. Intro. Dr. David Starr Jordan. Rand McNally, 1900. https://www.google.com/books/edition/True_Bear_Stories/TMlLAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=bear+stories+joaquin+miller&printsec=frontcover

Romero-Briones, A-dae, Enrique Salmon, Hillary Rennick, and Temra Costa. “Recognition and Support of Indigenous California Land Stewards, Practitioners of Kincentric Ecology. First Nations Development Institute and California Foodshed Funders, 2020. https://www.firstnations.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Indigenous-California-Land-Stewards-Practitioners-of-Kincentric-Ecology-Report-2020.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb. 2024.

“State Symbols.” State of California Capitol Museum. 2024. https://capitolmuseum.ca.gov/exhibits/state-symbols. Accessed 7 Feb. 2024.

Todd, William L. Original Bear Flag. 1846. Photo 1890. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Original_Todd_bear_flag.jpg Accessed 8 Feb. 2024.

Want to be notified when new posts are added? Subscribe to our newsletter.