In 1930, Herbert Eugene Bolton published his annotated translations of the Juan Bautista de Anza and Pedro Font diaries that recorded their experiences during their 1775 colonizing expedition (as well as letters and diaries of other notable explorers and clergy involved in Spain’s colonial project in Alta California). Bolton had spent years on his project, even exploring the terrain of the expeditions and identifying sites mentioned in the chronicles. It was a prodigious undertaking, and Bolton’s translations—now available and searchable online—are probably still the best known versions of these chronicles to readers of English.

Readers who dip into these diaries (especially readers who do more than dip) will not be surprised that the men who wrote them were creatures laced with Eurocentric prejudice, whose opinions, for example, about native people were dismissive, thanks partly to their own confidence in the superiority of their culture and its accomplishments. Font—easily the most fulsome of the diarists—could be especially harsh when rendering his opinions, as here, speaking of an encounter with “mountain Indians”:

Their food consists of tasteless roots, grass seeds, and scrubby mescal, of all of which there is very little, and so their dinner is a fast. Their arms are a bow and a few bad arrows. In fine, they are so savage, wild, and dirty, disheveled, ugly, small, and timid, that only because they have the human form is it possible to believe that they belong to mankind. (Bolton, V. 4, 145)

It’s worth noting that some of that prejudice seems to infuse the work of Bolton himself, but in a much different way. According to biographer Albert L. Hurtado, Bolton tended to romanticize his subjects: “. . . in retelling the accounts of missionaries and soldiers while characterizing them as heroes, Bolton gave his stamp of approval to a conquest that was sometimes brutal and frequently disastrous to Indian society” (174).

A more recent translation of Font’s diary by Alan K. Brown, which draws from material not previously available, attracts some of the same criticism. Historian Douglas Monroy, reviewing Brown’s volume, finds much to admire, but nevertheless notes that “unacknowledged in the lengthy introduction is the obvious issue of the nature of the Spanish mission. Was it conquest or civilization?” (419-20).

A different version of the Anza expedition story is offered by Vladimir Guerrero in The Anza Trail and the Settling of California. Guerrero tells the story from a third person perspective supported by his own translations of generous selections from the original diaries. This strategy allows him some narrative elbow room in order to emphasize another part of the story, the “racially diverse and yet integrated group of Spanish subjects who were the genesis of the California society, the Pilgrims of the State of California” (xi). Guerrero also stresses the important roles of two native men. One was Sebastián Tarabal, originally from Baja California, who had fled the harsh mission life at San Gabriel and eventually became a guide for Anza. The other was Salvador Palma, the chief of the Yuma nation, who became “an ally to Anza and integral to the success of the expeditions” (xii).

The National Park Service, which administers the Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail, has come to appreciate the need for expanding recognition of the role of indigenous people in the expedition, acknowledging that “Indigenous lifeways are underrepresented on the Anza NHT and on our website. We are committed to rectifying this gap and building relationships with tribal communities and partners.”

Building these relationships promises a kind of corrective to the NPS materials, but also, at least by implication, to the original diaries themselves (and other archival materials) that describe the presence of native people even as they disparage their cultures.

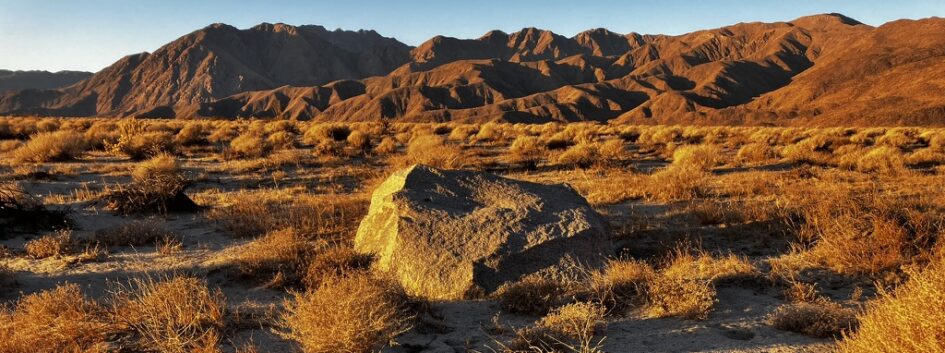

Good to keep in mind when reading “. . . the sweepings of the world”: Time Trailing the 1775 Anza Expedition in Borrego Springs.

Sources

“Anza Trail Values Statement: Creating Partnership, Investing in Communities.” Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail. National Park Service. Updated 8 August 2024. https://www.nps.gov/juba/learn/management/values-statement.htm. Accessed 16 January 2025.

Bolton, Herbert Eugene, Anza’s California Expeditions, Vol. 1: An Outpost of Empire. U of California P, 1930. California Digital Library. urn:oclc:record:1040017901.

—. Ed. and Trans. Anza’s California Expeditions, Vol. 2: Opening a Land Route to California, Diaries of Anza, Díaz, Garcés, and Palóu. U of California P, 1930. California Digital Library. urn:oclc:record:1039983801.

—. Ed. and Trans. Anza’s California Expeditions, Vol. 3: The San Francisco Colony, Diaries of Anza, Font, and Eixarch, and Narratives by Palóu, and Moraga. U of California P, 1930. California Digital Library. urn:oclc:record:1039966219.

—. Ed. and Trans. Anza’s California Expeditions, Vol. 4: Font’s Complete Diary of the Second Anza Expedition. U of California P, 1930. California Digital Library. urn:oclc:record:1039981729.

—. Ed. and Trans. Anza’s California Expeditions, Vol. 5: Correspondence. U of California P, 1930. California Digital Library. urn:oclc:record:1040017902.

Brown, Alan K. Ed. and Trans. With Anza to California 1775-1776: The Journal of Pedro Font, O.F.M. U of Oklahoma P, 2011.

Guerrero, Vladimir. The Anza Trail and the Settling of California. Heyday Books and Santa Clara University, 2006.

Hoffman, Abraham. “Bolton and the Birth of Borderlands History.” Rev. Herbert Eugene Bolton: Historian of the American Borderlands by Albert L. Hurtado. Journal of the West. Vol. 52, No. 1. 2013, pp 75-77.

Hurtado, Albert L. Herbert Eugene Bolton: Historian of the American Borderlands. U of California P, 2012.

Monroy, Douglas. Rev. With Anza to California 1775-1776 Translated and Edited by Alan K. Brown. The Americas Vol. 69, No. 3, 2013 , pp. 418 – 421. https://doi.org/10.1353/tam.2013.0052. Accessed 6 January 2025.

Want to be notified when new posts are added? Subscribe to our newsletter.