Introduction

My dad and I love skiing in the Sierras near Truckee together. Growing up, I’d sometimes get to play hooky from high school on a Friday in the winter to go on a father-daughter weekend adventure. Leaving from Hollister, I’d groggily get up and be in the car by 4:30 in the morning so we could hit the slopes at Sugar Bowl Ski Resort near Donner Summit when they opened. (And, I might add, we were skiing there before the Wall Street Journal dubbed Truckee “The Tiny Western Town That’s Quietly Become the Coolest Place to Ski” this past January). Racing down Bill Klein’s Schuss on Mt. Judah, we’d stop and catch our breath under a marker commemorating the emigrants who came through what became Sugar Bowl as they passed over the Summit in wagon trains.

Apart from reading the cool sign, I didn’t fully appreciate the area’s rich railroad history as a teenager–or the nine now-abandoned railroad tunnels that begin near the Mt. Judah parking lot at Sugar Bowl. First built in 1867 to protect Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) tracks from Sierra snow accumulations, the wooden snow sheds provided a solution to the vexing problem of keeping the notoriously heavy Sierra snowpack off the tracks. And no less a personage than the patriarch of travel writing, Robert Louis Stevenson, traveled through them and wrote about them on his 1879 westward journey to San Francisco in The Ameteur Emigrant.

This past August, some friends and I decided to see what all the fuss was about. We met in the abandoned parking lot near the entrance to the tunnels off the turn off to the Sugar Bowl Mt. Judah exit. (Note: the lot and tunnels are technically on private property, but according to the Donner Summit Historical Society, the owners have apparently never replied if people can use the lot for hikes and tours and hikers go through all the time without consequences). It was fun to have a different approach to Sugar Bowl and not be lumbering around in the parking lot weighed down by skis, and I got to think more about Theodore Judah–the namesake of Mt. Judah–the civil engineer who surveyed the route over the Summit for the Central Pacific Railroad. His work shortened the journey from New York to San Francisco from about six months to ten days by 1869, but he never saw the fruits of his labor; he died of yellow fever crossing the Isthmus of Panama in 1863 on a journey he likely would have avoided had his railroad been running across the country. Ready with our headlamps and flashlights, we set off for a five mile adventure on the part of the railway that the Sacramento Daily Union promised would be “a monument to the ability of American engineering” and was Judah’s brainchild. It was a foggy morning, and we hoped the mist would lift so we could see what would be an incredible view when we emerged from the tunnel and sheds.

Building the Tunnels: A Nearly Impossible Task

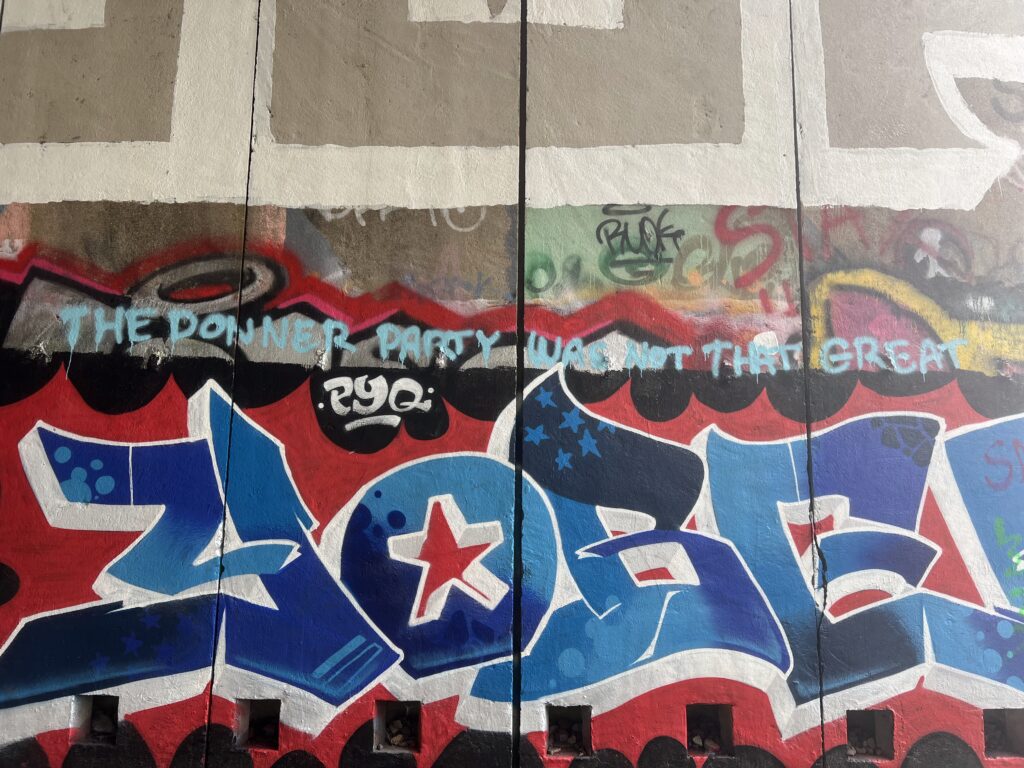

We began at Tunnel 6, the longest and most difficult tunnel the CPRR drilled through the Sierras, and one of the most significant engineering accomplishments of the nineteenth century. Taking a little over one year to complete by 1868, it stretches 1,659 feet through solid granite, one of the world’s hardest rocks. Carved out by hand by approximately 12,000 Chinese railroad workers, they began the project with sledge hammers and spade-shaped drill bits, making inches of progress a day. There was no ventilation, injuries were frequent, and the rock was carried out by hand. Black powder–a mixture of saltpeter, charcoal, and sulfur–wasn’t enough. Here, the CPRR used liquid nitroglycerin which they mixed on site. It doubled their progress, and was only used on this portion of the railroad (“The Use of Black Powder and Nitroglycerin on the Transcontinental Railroad”). The series of tunnels hug the mountain and iconically curve around Donner Lake, but now are used mostly by hikers and graffiti artists making attempts at Banksy-esque social statements.

As we entered the cold, dark gaping hole full of jagged granite that is Tunnel 6, the first thing we noticed was the spray painted tribute to the Railroad Chinese. Spelling errors aside, the depiction of the Railroad Chinese was a good reminder of the men who did the hardest work on the railroad. Historian Gordon H. Chang delves into their history in his newer book Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad, adding much-needed research to the tragic story of the Railroad Chinese. The Railroad Chinese worked around the clock, despite the ferocious Sierra winters and sweltering summers. They faced disease, frostbite, unequal (and very low) pay, discrimination, and death. Many Railroad Chinese lived in the open in the Sierra, even during the winter, boring not only tunnels in the granite but snow tunnels to their rudimentary dwellings. Summit Camp, at over 7,000 feet, became a small town as the men carved their way through the mountains (107). Their work was key to connecting the United States and shortening travel time across the country from about six months to ten days, but they received little gratitude for their labor. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, thanks to pressure from the California congressional delegation, preventing Chinese immigrants from entering and working in the US until WWII. By 1896, most of the Chinese were out of Truckee, being subject to ongoing racial violence and a boycott of Chinese businesses (231-32).

The hardest work on the Summit began in 1867, and the winter of 1867-68 was one of the heaviest on record. Certainly memories of the Donner Party’s ill-fated expedition twenty years prior would have been on people’s minds. But construction of the tunnels continued while forty-four storms hit the Summit, snowdrifts were over forty feet, temperatures were frequently below freezing, and blizzard winds over one hundred miles per hour hit the pass (102). Snow quickly covered living spaces, and snow slides killed many. (The storms are infamous, as Terry Beers writes about in his piece on George R. Stewart’s Storm, an ecological novel about a blizzard over Donner Summit).

An Engineer’s Brief (but Inspired) Prose

When the snows stopped, however, the scene was breathtaking. I found a description of it by John R. Gilliss, the chief engineer of the construction of the CPRR across the Sierra Nevada, and was almost giddy to read his description of the Summit at night. I was delighted that a chief engineer would be so moved by the scene that he included some comments appreciating the landscape tucked in between extremely dull technical reports to a group of other engineers about how the CPRR designed the snowsheds.

From this road [the Pass to the descent toward the lake] the scene was strangely beautiful at night. The tall firs, though drooping under their heavy burdens, pointed to the mountains that overhung them, where the forest that lit seven tunnels shone like stars on their snowy sides. The only sound that came down to break the stillness of the winter night was the sharp ring of hammer on steel, or the heavy reports of the blasts. (154-55)

On November 30, 1867, Summit Tunnel 6 was finished. Railroad tycoons Leland Stanford, E.B. Crocker, Charles Crocker, Mark Hopkins, two senators, “ladies and members of the press” visited the completed engineering feat. Declared the Sacramento Daily Union in an article called “The Mountains Overcome,”

The flag of the Union was immediately planted near the spot, fitly signifying that an event had occurred which, more than any other, assures the continued unity of this great republic. For the completion of a railroad across the Sierras removes the only obstacle which has been regarded as insuperable to a vital connection between the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. For California this means much, but it means more for the country at large and for mankind. The people of this continent are no longer severed by mountain barriers which would make them two nations, diverse and hostile.

Indeed, in the aftermath of the Civil War, witnessing such a physical reminder that the nation was one would have been moving and awe-inspiring. As we exited Tunnel 6, my friends and I were not swept up with exuberant patriotism, but we could, however, easily appreciate the sense of triumph people had conquering the Sierras. Perhaps if we could see Donner Lake through the thick fog we would have felt like prouder Americans.

A Long, Annoying Journey

We pushed on into a cold, damp snowshed. I’m sure many passengers found the snowsheds too gloomy; the mist filtering in through the windows to the left never lifted and added an eeriness. No magical Sierran tableau was visible to us. Today, the sheds are mostly concrete, but they were originally timber–65 million feet of timber stretching over 37 miles. In fact, according to a Donner Summit Historical Society brochure, the CPRR used so much timber that the mills couldn’t keep up, so at times, stripped round logs were used in portions of the sheds (“The Snowsheds of the Central Pacific Railroad on Donner Summit”).

Our obstructed view was a bit similar to what one rather grumbly correspondent from New Zealand experienced when he took the train on the newly completed rail as part of his journey. He describes every portion of the journey from the Great Plains to the Great Salt Lake, over the Sierras, and down into Sacramento to San Francisco with great care for detail and rather amusing complaints. Going to bed in the cars was “an odd experience,” and the food when they stopped in Cheyanne was unappetizing: “The chops were generally as tough as hunks of whipcord, and the knives as blunt as bricklayers’ trowels. One of our hosts told me that he kept three fishermen and two hunters to provide food for the trains. I told him I wished he would keep his meat a little too.” His frustration was most palpable, however, when he passed over Donner Summit:

The scenery to the right, where several lakes show themselves far below the track, is very beautiful; but it is spoilt by the snow-sheds which cover the line for some 30 miles, and afford only glimpses of the country far beneath the traveller. These sheds are made of sawed pine timber, covered with plank, and a more convenient arrangement for a long bonfire I never saw. This part of the line must be burnt some day, as the chimney of every engine goes fizzing through it like a squib, and the woodwork is as dry as a bone.

As I made my way through the tunnel, I could at least be happy that my friends and I weren’t stuck in a crowded train car with memories of bad food, noxious odors, and anxiety over burning to a crisp inside a snowshed.

The correspondent brings up an important point, however, about the tinderbox nature of the snowsheds. Eminent railroad historian Richard Orsi in Sunset Limited: The Southern Pacific Railroad and the Development of the American West 1850-1930, explained the results of constant threat of the snowsheds and surrounding forest catching on fire. The Southern Pacific Railroad built a lookout station on Red Mountain in 1876. The mountain, as the name describes, is red and bare, about two miles north of and 2,000 feet above the fire station at Cisco, giving about fifty-mile panoramic views of the surrounding forest. Two-man crews kept watch around the clock, giving half hour updates telegraphing (and later telephoning) the Cisco station with condition updates. It was part of a larger lookout system that worked: according to Orsi, fire-loss per mile was less than one-half the average for all steam railroads in the US, and the lookout system was praised for its technological innovation for successful wildfire control. The Red Mountain lookout operated until 1934, when the last wooden snowshed in that area were torn down in favor of flame-resistant concrete (389-90).

“A Grateful Mountain Feeling at my Heart”

Perhaps the sickliest traveler ended up appreciating the limited views from tunnels and snowsheds the most because of what they symbolized. As I wrote about in “The Old Pacific Capital,” Robert Louis Stevenson set off from Glasgow to Monterey in 1879 to be with his future wife, Frances Matilda Van de Grift Osbourne (“Fanny”). He paid “immigrant” fare, where passengers often slept on the floor and food was too costly or unavailable. Camille Peri, author of A Wilder Shore: The Romantic Odyssey of Fanny and Robert Louis Stevenson that importantly examines their relationship also from Fanny’s perspective, explained the physical toll Stevenson’s journey took on him: it took Stevenson about three weeks to make the journey from Scotland to Monterey, and he contracted malaria on the train. He also suffered from malnourishment and pleurisy, a lung condition that makes it painful to breathe. He relied at least once on laudanum as a remedy, which probably only made him feel worse (147).

In Ogden, Utah, he transferred from the Union Pacific to the Central Pacific cars for the final leg of his journey. “The change was doubly welcome; for, first, we had better cars on the new line; and, second, those in which we had been cooped for more than ninety hours had begun to stink abominably,” he recalled. He wasn’t in the best shape, then, when the train entered California and through the Truckee Canyon, but he was the happiest traveler. He was that much closer to seeing Fanny:

Of all the next day I will tell you nothing, for the best of all reasons, that I remember no more than that we continued through desolate and desert scenes, fiery hot and deadly weary. But some time after I had fallen asleep that night, I was awakened by one of my companions. It was in vain that I resisted. A fire of enthusiasm and whisky burned in his eyes; and he declared we were in a new country, and I must come forth upon the platform and see with my own eyes. The train was then, in its patient way, standing halted in a by-track. It was a clear, moonlit night; but the valley was too narrow to admit the moonshine direct, and only a diffused glimmer whitened the tall rocks and relieved the blackness of the pines. A hoarse clamour filled the air; it was the continuous plunge of a cascade somewhere near at hand among the mountains. The air struck chill, but tasted good and vigorous in the nostrils—a fine, dry, old mountain atmosphere. I was dead sleepy, but I returned to roost with a grateful mountain feeling at my heart.

I’ve been visiting Truckee all my life and this is Truckee air. Stevenson gets it.

The train continued on, up and over the Summit and through the snowsheds:

When I awoke next morning, I was puzzled for a while to know if it were day or night, for the illumination was unusual. I sat up at last, and found we were grading slowly downward through a long snowshed; and suddenly we shot into an open; and before we were swallowed into the next length of wooden tunnel, I had one glimpse of a huge pine-forested ravine upon my left, a foaming river and a sky already coloured with the fires of dawn. I am usually very calm over the displays of nature; but you will scarce believe how my heart leaped at this. It was like meeting one’s wife. I had come home again—home from unsightly deserts to the green and habitable corners of the earth.

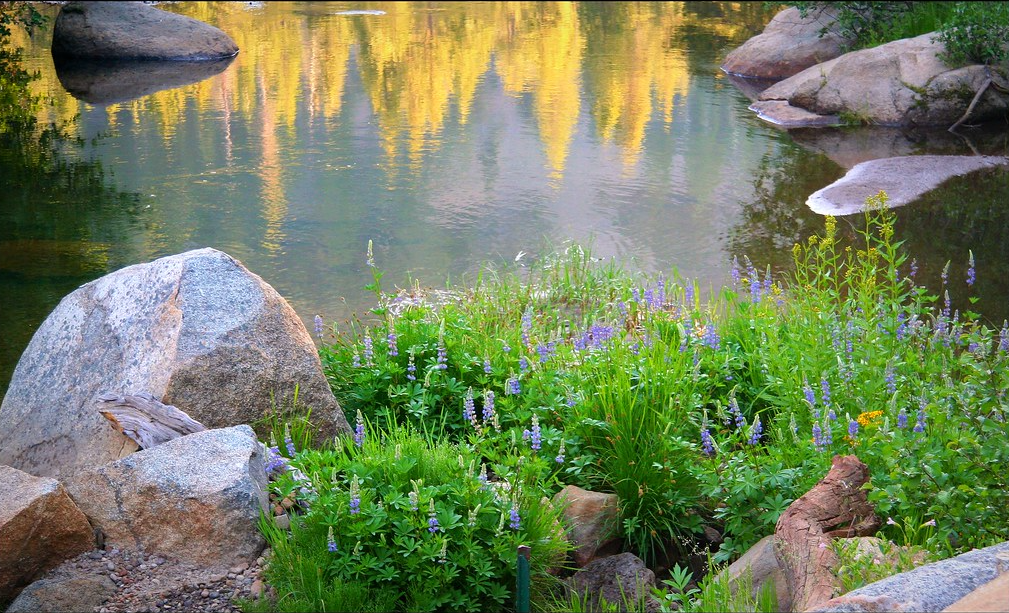

He’d spotted the Truckee River, and the contrast between the “desolate” desert scenes of Utah and Nevada with Sierra greenery was overwhelming. (What he might not have realized was how uninhabitable the Summit is during winter, but I’ll let it go).

I admit, I’ve felt similarly driving through Nevada desert and suddenly entering the lush Sierra landscape: you go from unending desert views, to glimpses of the back of the towering snow-capped Mt. Rose, and then suddenly, you’re in the Truckee Canyon, following along the train tracks and enjoying watching the Truckee River rush by. Stevenson, however, is a bit more exuberant, but I suppose that’s understandable after being stuck in a crowded train car traveling across the country:

Every spire of pine along the hilltop, every trouty pool along that mountain river, was more dear to me than a blood relation. Few people have praised God more happily than I did. And thenceforward, down by Blue Cañon, Alta, Dutch Flat, and all the old mining camps, through a sea of mountain forests, dropping thousands of feet toward the far sea-level as we went, not I only, but all the passengers on board, threw off their sense of dirt and heat and weariness, and bawled like schoolboys, and thronged with shining eyes upon the platform, and became new creatures within and without. . . . For this was indeed our destination; this was “the good country” we had been going to so long.

Ignoring the hyperbole, California promised him Fanny. Stevenson observed trains of emigrants going past his train back east and hoped they’d all struck it rich in the golden state, however unlikely; by the time he saw “the good country,” he could only think of all California had to offer. And California changed his life: he ended up soon with Fanny in Monterey, and honeymooned with her in Silverado in Napa where they “squatted” in a small cabin under Mt. Helena. Although he only stayed in California a little over a year before they went to Switzerland for his health, his time in the state not only contributed to The Ameteur Emigrant, but also inspired such classics as Treasure Island.

The Donner Party Was Not That Great

We never saw the fog lift that day to see Donner Lake from above. My friends went back a few weeks later to snap some photos and said it was incredible–the type of view that were Stevenson joy-worthy. Today, as Smithsonian Magazine’s History Correspondent Shoshi Parks reported, there’s a movement for the tunnels to be declared historical monuments. And I agree wholeheartedly; currently, there are some hikers and school groups, but also a lot of graffiti–too many references to Taylor Swift (both for and against) adorn the tunnels when it’s a true testament to the labor of the Chinese who sacrificed their lives here. One tag that made my group stop and chuckle was one that read “The Donner Party Was Not That Great.” While it might be wrong to compare losses of life, it allowed for contemplation of the sheer amount of pain and suffering that happened around the shores of Donner Lake. And hopes that the memory of the lives lost will be honored and preserved.

Sources

Beers, Terry. “George R. Stewart’s ‘Storm.’” Rewriting California, https://rewritingcalifornia.com/george-r-stewarts-storm/. Accessed 5 February 2025.

“The Central Pacific Railroad.” Sacramento Daily Union, Vol. 32, No. 4854, 18 Oct. 1866, https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SDU18661018.2.2. Accessed 5 February 2025.

Chang, Gordon. Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese who Built the Transcontinental Railroad. Boston, 2020.

Diamond, Anna. “The Tiny Western Town That’s Quietly Become the Coolest Place to Ski.” Wall Street Journal. 24 Jan. 2025. https://www.wsj.com/lifestyle/travel/truckee-tiny-western-town-quietly-become-coolest-place-to-ski-d7e3c3e3. Accessed 25 Jan. 2025.

The Donner Summit Historical Society. The Donner Summit Heirloom: History and Stories of the Donner Summit Historical Society. No. 47, 2012, http://www.donnersummithistoricalsociety.org/PDFs/newsletters/news12/july12.pdf.

Elrod Cardenas, Emily. “Robert Louis Stevenson’s ‘Old Pacific Capital.’” Rewriting California, https://rewritingcalifornia.com/robert-louis-stevensons-old-pacific-capital/.

“From Chicago to San Francisco by Rail.” Hawke’s Bay Herald, Vol. 14, Issue 1122, p. 3, 28 Jan. 1870, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/HBH18700128.2.12. Accessed 5 February 2025.

Gilliss, John. “Tunnels of the Pacific Railroad.” American Society of Civil Engineers, Transactions. New York, 1870. https://assets.ctfassets.net/ym7g6wle8tnv/9w3pz2LUPjBgO2Rf1wl0N/4f98626816fc0c8d3d4f868c798e89d3/Tunnels_of_the_Pacific_Railroad__John_Gilliss__1870.pdf. Pdf file.

“The Mountains Overcome.” Sacramento Daily Union, Vol. 34, No. 5204, 2 Dec. 1867, https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SDU18671202. Accessed 5 February 2025.

Orsi, Richard J. Sunset Limited: The Southern Pacific Railroad and the Development of the American West 1850-1930. Berkeley, UC Press, 2005.

Parks, Shoshi. “The Quest to Protect California’s Transcontinental Railroad Tunnels.” Smithsonian Magazine. 12 Jan. 2022. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/the-quest-to-protect-californias-transcontinental-tunnels-180979382/. Accessed 5 February 2025.

Peri, Camille. A Wilder Shore: The Romantic Odyssey of Fanny and Robert Louis Stevenson. Viking, 2024.

“Snowsheds.” Donner Summit Historical Society. http://www.donnersummithistoricalsociety.org/pages/exhibits/snowsheds.html#:~:text=After%20that%20winter%20the%20Central,tons%20of%20bolts%20and%20spikes.&text=thousands%20of%20workers%3A%20fire%20train,%2C%20carpenters%2C%20and%20snow%20shovelers. Accessed 16 Feb. 2025.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston Edition, Vol. 2. Project Gutenberg, 22 Nov. 2009. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/30527/30527-h/30527-h.htm. Accessed 16 Feb. 2025.

“The Use of Black Powder and Nitroglycerin on the Transcontinental Railroad.” https://www.lindahall.org/experience/digital-exhibitions/the-transcontinental-railroad/01-black-powder-nitroglycerin/#main-content. Accessed 14 Feb. 2025.

“Trouty Pools” courtesy Annette Elrod.

Want to be notified when new posts are added? Subscribe to our newsletter.